Once I discovered the ecstatic experience of being absorbed in imaginative worlds through reading Little Men and then other books, I immediately reasoned, as I’ve said, that if I could spend my life creating such worlds, I’d be happy.

I didn’t pause to think how reading Little Men necessarily equated to a gift for launching my own vivid and continuous fictional dreams. Thinking about the question now, so many years later, I find the inference fraught with the difficulties I’d soon enough encounter, but still understandable and even brave.

Whenever we enjoy a literary work, a painting or sculpture, a film, or a piece of music, we are secondary creators of the work. The story, the film, the music doesn’t take wing until we enter into it and bring it to life in our own imaginations. To the degree and depth, we become, so to speak, “co-creators” with the author or the composer, we have a more or less powerful experience of the work, which is especially true with the greatest works of art that challenge our own imaginative capacities to their limits.

This experience is shatteringly powerful for those who feel a calling to the arts and evokes love. We long to return to what we love. A calling to the arts is, especially at the beginning, a love affair.

At first, I did not understand that I had fallen in love not only with the ecstatic experience of being caught up in a fictional dream but also with the means of transport there: language. (I want to register this as I’ll return later to the importance of the artist’s fascination with his materials.)

I think of all the things I have done in my life, many of them “pragmatic”—in what has usually turned out to be a grand waste of time—the one thing in which I find solace and peace is the service I have rendered to what I have loved. A calling to the arts is first of all a love story, in which the beloved dictates her terms to a grateful pursuer.

There’s a bridge that gets crossed in such an experience: a door that opens. We grasp intuitively how the Ur-work with which we have become enraptured makes available to our own imaginative life powerful methods of transport into what’s unknown but somehow sought. A place outside ourselves from which perhaps we might see a means of escape from the prison of the self. A new way of being based on understanding our inner contradictions, and how these might be reconciled.

For even as children, as we become self-conscious, we experience ourselves as a problem to ourselves. How do we fit into the world? Find our place? By the time we enter adulthood, almost everyone’s thoughts have traveled along the lines written by Elizabeth Bishop in “Questions of Travel.”

"Where is there a place for you to be? No place."

So much of who we are and what we are about, our purpose, escapes our own understanding.

Let’s put it this way: anyone who says he has life all figured out is simply lying. Understanding who I am and what I should be doing in life and why makes of my own thoughts a chaotic and often cacophonous dialogue. A similar racket seems to be going on in everyone’s head.

The existentialist philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, claimed that everyone’s fundamental project—what each strives for—is to become a thing-in-itself or self-sufficient in a godlike way. Unfortunately, the human being is a thing-for-itself, bedeviled by his freedom and the continuous process of becoming (or change) this entails.

One thing that happens in the ecstasy of artistic creation or re-creation in an audience member is that we are brought through the familiar maddening contradictions of life to places of repetition, recognition, and reconciliation. We follow a path, however different from our own, that leads us to feel that we are retracing our own steps, invoking our own memories. The writer then articulates elements of this journey that we recognize, even if, sometimes especially if, they have escaped our own powers to name them. This finally leads to reconciliation with the experience presented and our own experience. It leads to that “sense of an ending” and the peace entailed. What the Greeks called catharsis.

Endings often have an eschatological dimension, implying a “happily ever after.” Could such be available to the creator himself and his audience? That’s at least the hope—that we learn something. Perhaps something of transcendent value. Something that endures in the face of death or reaches beyond it.

In medieval times, “to teach and to delight” summarized the purpose of the arts. That did not mean that the primary purpose of the arts was didactic. Rather, it implied that the world had a coherence that could be discovered by the artist and conveyed to his audience.

I am giving of my bountiful self to myself as the outpouring of the font of inspiration that I am.

This relativizing of what we derive from art leads us to value the performative aspects of an artwork—the cleverness of its conception and the skill of its execution—above everything else. For if the artist is only expressing his own thoughts and feelings, without any implication that the artwork might make claims upon us beyond our attention, then the delight the artwork supplies becomes the only criterion by which to judge it.

Artists talk about the importance of expressing themselves and their art as “therapy,” but I think that’s nonsense. I doubt many artists of real value have entered upon their work as a means of self-expression. Many artists don’t lack for ego, of course, but think of the conceit an expressive theory of art implies. I am giving of my bountiful self to myself as the outpouring of the font of inspiration that I am.

Self-expression is not why artists feel called to create. It’s also not why we read poetry and fiction, visit art galleries and museums, watch films, and listen to music.

Even bad artists know better. There’s quite a terrible limited TV series that came on not long ago, A Family Affair, starring Nicole Kidman, who plays a writer. When her longtime editor, played by Kathy Bates, asks her why she writes, Kidman says, “It’s my way of explaining things to myself I don’t understand.”

That may be the only spot on observation in that whole series, but it’s one of the artist’s primary motivations. The arts are a means of exploring questions of value and purpose, which, by their nature, are not subject to scientific investigation. As George Steiner puts in in Real Presences:

They [the major forms of art] enact, as I have noted, a root-impulse of the human spirit to explore possibilities of meaning and of truth that lie outside empirical seizure or proof. Pre-eminent in this moto spirituale is the inference, either implicit or explicit, of the preternatural agency, of the borderland. So very much in Western art and literature enlists the proposal that we are close neighbours to the unknown, that we move among order of pragmatic substance themselves permeable to that which lies on the other side, which acts from beyond ‘the shadow-line (p. 225).

Steiner connects this “root-impulse of the human spirit” to what lies beyond the merely human or at least to the possibility that something or someone “lies beyond the other side.” He alludes not to the self, but to what is distinctly beyond the self: the “real presence” of God—or at least God’s possibility—in creation and thus in the greatest of human creations. In fact, he claims that this “real presence” accounts for what makes any artwork great.

What I found as a I began to write was that storytelling served as the means by which I could explore the questions closest to my heart. The capacity or art to take me out of myself was essential to its power as a means of discovery. That a calling to the arts entails a religious quest—Steiner’s moto spirituale.

We’ve arrived at our own borderland between a religious and a secular understanding of the artistic calling. Few artists may want to cross this divide with me. For one thing, it’s bad for business, and it’s hard enough to make a living as an artist.

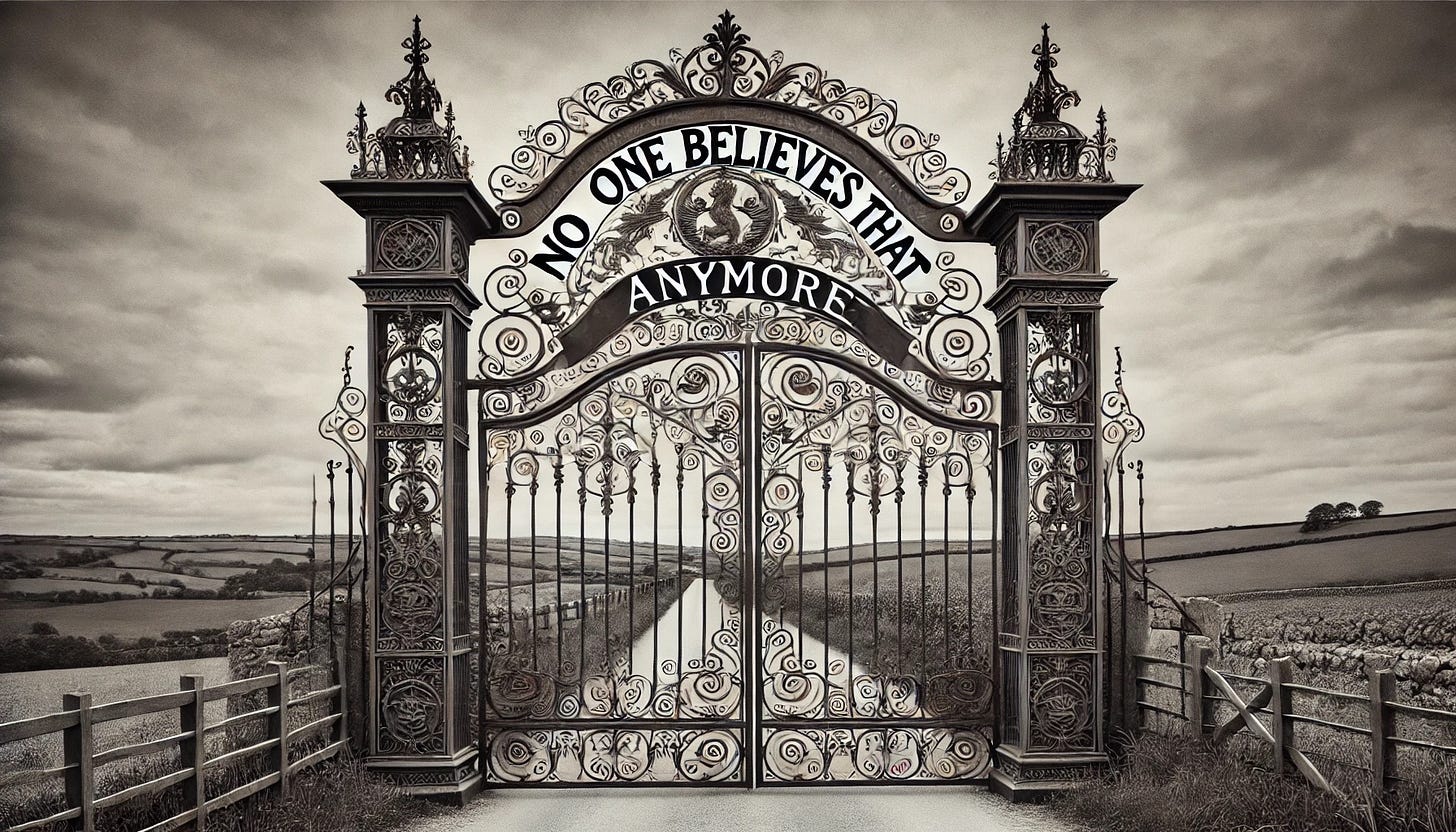

There’s a dreadful gate at this borderland’s crossing. It’s inscribed: “No one thinks like that anymore.” For most that’s the end of the discussion.

Why? Two strains of thinking account more than others for the secularization of the public imagination. The latter of these has become an ideological straitjacket.

Today, most have come to accept that we live in a universe brought into being and governed purely by chance.

Since The Origin of the Species, Darwinian theory has been used to undermine religious belief. As the twentieth century turned into the twenty-first, the “new atheists,” Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, and Daniel Dennett wrote a spate of books to hammer the last nails into God’s coffin. In River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life, Dawkins says:

The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.

Neo-Darwinian theory, these writers are at pains to point out, does not allow for any coziness with the divine.

Still, many try. It is common to hedge against Dawkins’s understanding of the world’s pitiless indifference by imagining God somehow sneakily influencing the randomness.

New Agers and their latter-day followers adopt views similar to the Hindu over-soul (or Brahman) in which God is conceived as an intelligence present in all things—that seems to have been Einstein’s view. Anthropomorphic shadings not-so-subtly soon creep in. So, we speak of what the universe “wants” for us, or recognize the spark of divinity within us that is echoed in the stars, etc.

Stephen Hawking remained intent on foregrounding the nihil in ex nihilo. In The Grand Design he argues,

Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist.

A natural “law” like gravity without a preexisting nature? Come again?

Still, few want to venture forth against the scientific magisterium. The infinite, personal God at the center of Judaism and Christianity and the implications of this being’s existence can and should be forgotten by anyone in-the-know.

Beckett’s line comes to mind:

They give birth astride a grave. The light flickers, then it’s night once more.

The second secularizing strain of thought stems from skepticism as to the accuracy of human perception and thus the power of language to communicate an accurate view of the world.

This has a long history, which goes back at least to Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804), who divided the phenomenal (the world as we perceive it) from the noumenal (the world as it is in itself). The existence of God guaranteed for Kant a close correspondence between perception and reality.

But the thinkers who followed Kant, like Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Heine, had an ever-increasing animus toward any conception of a logos—of the world being brought into being by a divine creative reason, which had served as the foundation of the unity between word (language) and world (cosmos).

Nothing in the academy was more readily and universally jeered than any mention of “reality,” as if such a thing could be known or even existed.

During my formal education, I encountered the evidence of this skepticism in what were to me bewildering assumptions among my professors. Radical doubt as to the correspondence of human perception with the true nature of the world in which we live reigned. Even the efficacy of reason, outside scientific domains, enjoyed only a circumscribed acceptance, when it was accepted at all. Nothing in the academy was more readily and universally jeered than any mention of “reality,” as if such a thing could be known or even existed.

Why then was I studying literature, philosophy, and the other humanities if not to gain a greater understanding of the world and my place in it? Why were a cadre of professors putting me through the rigors of their disciplines if neither they nor I could ever discover anything real?

My professors had an answer or at least an attempt at one. My education took place in the latter days of the “new criticism.” We were only to consider the text itself, and so whatever claims an artwork made about truth and its moral implications were transposed into sources of aesthetic interest. The house of aesthetics included all manner of such propositions, and they could all be welcomed as grist for the pleasurable and infinitely varied game of criticism.

It was common among my professors to aver that they studied literature—and we should as well—for no other reason than that they enjoyed it.

My professors’ liberalism was soon enough succeeded by “critical theory” advanced by the Frankfurt school of philosophy. In the 1970s and 1980s this generated its now-familiar offshoot “critical race theory.”

(Those interested in the intellectual history behind these developments should consult Jonathan Leaf’s brilliant A Short Critical History of Philosophy, which is being released in serial form at his Substack.)

The value of art lies in its utility for purposes external to the art itself.

Foucault and thinkers like him, including Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Paul de Man, were heavily influenced by Marxism. As such, they dispensed with any transcendent meaning to art, especially the notion that art might testify to a creative principle at work nature. In their view, artworks acquired their value to the extent they could be used as tools for other purposes.

This bears restatement. The value of art lies in its utility for purposes external to the art itself.

Politics is said to be “war by other means.” Critical theory saw art as thoroughly political and thus part and parcel of class warfare.

This view became in the old Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellites what was known as “socialist realism.” The state supported artists as long as they were willing to produce works that celebrated communism’s heroic struggle against capitalism, elevated champions who sacrificed their own ambitions to the greater wisdom of the working class and praised the status quo as the best of all possible worlds.

Socialist realism produced the world’s ugliest buildings, a blight of monumental statues, and monotonously heroic novels and paintings.

Happily, the socialist realist wall started comin’ a tumblin’ down with Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and the Berlin Wall soon followed.

Nevertheless, critical theory—or what I’ll call the “new socialist realism”—has become the reigning theory of art in the West in its “critical race theory” iteration.

The next generation of academics after my professors and many influential artists under their tutelage became enticed by critical theory and its successor, critical race theory, because it presented the opportunity to enlist in a grand utopian project. For if artistic works testify to evolving standards and power structures within society, then perhaps the artist can fast-forward the dawn of new and better eras by incorporating into their works the vanguard of society’s best thinking.

Critical race theory, as is now becoming widely known, enlarged and redefining oppressed classes with “marginalized groups,” who were disadvantaged by the reigning power structures either economically or socially. The patriarchy, systemic racism, cisgender normativity, anthropocentrism, etc. became for those ascribing to critical race theory synonymous with the capitalist ruling class; in other words, the enemy that must be destroyed through “transgressive art” meant to shatter every form of oppression.

As the old socialist realism produced ugliness and a mind-numbing predictability, so does the new socialist realism (aka critical race theory). This has had its most devastating effect in American cinema, producing characters devoid of humanity, plots that inevitably reveal corporations as the puppet masters of evil, and a preachiness as intolerable as the demand in faith-based films for scenes of spiritual conversion. Actually, even more intolerable.

The Oscars officially endorsed the new socialist realism on September 8, 2020, when The Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences (AMPAS) declared that no film would be considered for a Best Picture award as of 2024 without meeting two of the following four criteria: 1) On-Screen Representation, Themes, and Narratives – the cast must include “underrepresented racial or ethnic groups”; 2) Creative Leadership and Project Team – key people behind the camera have to be from underrepresented groups; 3) Industry Access and Opportunity – the company is obliged to hire production assistants from underrepresented groups; and 4) Audience Development – members of underrepresented groups should be involved in marketing and distribution and/or the film targeted to minorities.

The roll call of films and limited TV series launched and highly praised as a result of the critical race theory mindset is now without number. That a small film built on a paranoid racial fantasy like Get Out could be nominated in 2017 for Best Picture and win Best Screenplay speaks volumes and not in a good way. Virtue-signaling has nothing to do with creating great films. A movie like Gran Torino is great precisely because it’s honest about its characters’ flaws.

What few of those ascribing to critical race theory seem to understand is that Foucault’s critique applies just as much to today’s artists as it does yesterdays. In other words, for all your utopian fantasies, you are only the mouthpiece of the social structures that have put you in a privileged position. There’s no possibility that you are speaking “truth to power” because there’s no knowing the truth or even the possibility of there being any truth that can be known. At best, you are a different kind of propagandist, serving different masters than those you despise.

As far as I can tell, there’s little self-consciousness among artists how a thoroughgoing relativism, based on class warfare, as adumbrated in critical race theory, vitiates any notion of the arts as anything more than sophisticated propaganda.

I have met a few people in entertainment who are honest about this. In discussion with a producer once, I said something about the transcendent importance of beauty, to which he replied that he believed in no such thing.

I asked what he made of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel.

Very good propaganda, he replied. In a masterful way, the Church has used storytelling, he said, to maintain its power.

Not many can make such brutal assessments and live with themselves. They stop themselves from thinking about it. They find, I imagine, such reflections about how we arrived at agnosticism as today’s default position as more or less uninteresting. That’s just the way it is They are content in the knowledge that no one believes that anymore.

For their purposes, the fascinations of the human condition and the imaginative possibilities of the immanent (the here and now) are sufficient. Most art in our time is thoroughly secular and content to be so.

If the subjects of the arts are now being dictated by a new reigning ideology, they are willing to follow such guidance, even profess undying allegiance to it, because the people writing the checks demand it. How different is this from what pertained in the old Soviet Union?

I’m reminded of an exchange that takes place in one of the Coen brothers’ films, Barton Fink. It presents the two ways most react to the current situation.

John Tuturro plays an earnest young playwright who comes from New York to Hollywood to write for the movies in the 1940s. He’s a leftist true believer.

When he goes into his usual revolutionary spiel to an older Southern writer, known in the film as W.P. Mayhew—likely a fictional representation of William Faulkner—the the older man replies, “’Ah juss’ like maykin’ thangs up.”

I could have taken one of these approaches to the progressive zeitgeist of my time, either becoming a willing believer or placing the whole matter in parenthesis, but for this: I could not get away from my desire, intuition, and perception that the world around me and my life within it meant something. A meaning that had a value and an import that demanded to be understood. That called out to be understood.

Meaning in our times is a “stone of stumbling” and “a rock of offense,” as Isaiah writes of the Messiah (8:14).

It’s hard to get away from, though.

Think of Richard Dreyfuss in the movie, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, going not-so-quietly mad at the family dinner table as he tries to sculpt a replica of Devils Tower out of the mashed potatoes. He’s desperately trying to understand the calling aliens have implanted in his mind to come meet them in Wyoming. In exasperated helplessness, he can only exclaim, “This means something!”

That was my feeling, and I’d suggest it’s every artist’s feeling about his vocation: This means something.

How does someone who feels such a calling reconcile this phenomenon in his personal experience with the meaninglessness implied by all things being governed strictly by chance?

Or dedicate himself to the grueling work art often entails only to serve as a mouthpiece for his socio-economic class, with all its oppressive prejudices? (Because short of critical theory’s utopia, every class must be considered an oppressor class.)

Next, we’ll consider the strangely exalting experience of artistic practice and how it leads to unforeseen discoveries. We’ll consider whether another way of thinking about a calling to the arts might serve as an avenue for talented people to produce the best art of which they are capable, and, simultaneously, be as fully alive in the other aspects of their lives as this broken world allows.

The opening lines of Keats' Endymion -- "A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:/Its loveliness increases; it will never/Pass into nothingness..." He ends Ode on a Grecian Urn with these words: "Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

Yes!