“Movies aren’t made, they are forced into existence,” said the famous producer, Laura Ziskin. Mark Joseph’s Reagan might be seen as a case in point, as bringing Reagan to the screen involved an epic, nineteen-year struggle.

The film debuted this past Labor Day weekend and shocked the box office with a 98% audience approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes' fan-based Popcornmeter, and gross box office receipts to date of $30 million. It reached #1 at the box office on September 5th and #1 on the DVD/Blu Ray charts in October.

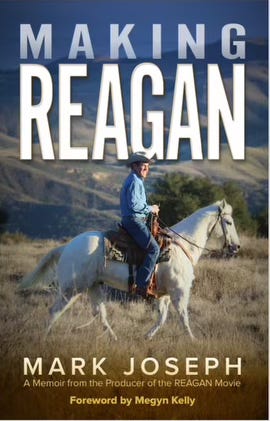

Joseph recounts his 19-year quest to make the biopic in his new book, Making Reagan, which may be a work of equal significance to the film itself. It should be of immense help to up-and-coming filmmakers for its behind-the-scenes look at making what I take to be the most important type of artistic creation, a rendering of its subject from as much of an eternal perspective as humans are granted to know.

Despite what its critics have said, it’s not a “faith-based” story, in which the hero’s faults are air-brushed away, the villainous are obviously to be despised, and it’s only a matter of time before the message writ large is blindingly clear.

Nor is it a movie in which the religious elements have been removed for the sake, ostensively, of appealing to a general audience. The renowned religion columnist, Terry Mattingly, observed that religion often becomes the “the ghost” in many stories, explaining that it is “the invisible thing that moves and motivates.” Without it, many characters and their actions become inscrutable.

Examples of such are everywhere, but my favorite is Wallace Stegner’s Angle of Repose, a brilliant depiction of the American frontier in the late 19th century from which religion is scrupulously—and, on reflection, ludicrously—absent. (It’s still a fine book.) Angelina Jolie’s telling of Louie Zamperini’s story in Unbroken suffers from the same anti-faith bias.

Mark Joseph set out to tell his story whole, with his hero’s flaws, as well as virtues, on full display. In other words, he wanted to make a real movie. Perhaps a great one.

In retrospect, Reagan, the most consequential president since FDR, seems an obvious choice for a biopic. Yet, no major movie had been made about him when Joseph started to do so in 2006. This could only be due to the leftist bent of the industry. Also, to my mind, the myopia of the right when it comes to influencing culture. As even his harshest critics acknowledge, Reagan, with the help of Pope Saint John Paul II, won the Cold War. Like the Pope, Reagan was also shot and nearly assassinated. By any measure, that’s drama.

In fairness, a deeper problem existed than Hollywood’s bias. Reagan, the man, was an enigma to many. Even the president’s official biographer, Edmund Morris, found his subject “inscrutable.”

Reagan inspired fierce loyalty among advisers like Edwin Meese, William Clark, and George Shultz and was famously friends with the leader of the Democratic Party in the House, Tip O’Neill. The deepest aspects of his character and most particularly their wellsprings—the sources of his motivation—eluded them, however. He befriended others easily, while remaining hard to know.

Two walls ringed the president’s interior life.

His wife Nancy Reagan and he dwelt within the first, which created an inner sanctum into which Reagan’s own children often feared to step.

Beyond even Nancy’s realm, lay a personal privacy as carefully guarded as Reagan’s appearance was kempt, with never a hair out of place. Many put this down to Reagan’s alcoholic father, whose public drunkenness shadowed Reagan’s childhood.

The mystery of what drove Reagan and what seemed to many his perpetual boy scout behavior left his critics to conclude that he simply wasn’t very bright. He remained the B-movie actor in Bedtime for Bonzo: all cheery appearance and empty-headedness, spouting lines from the conservative playbook. It wasn’t until his personal letters were published, revealing the depth at which he read and engaged with ideas, that a grand reassessment began of his personal gifts and how these led to the historical achievements of his presidency. Successors like Barack Obama would aspire to be in Reagan’s league as a pivotal figure, if in another direction.

The question remained as to how to account dramatically for Reagan’s singular impact on history. Who was he?

Making Reagan connects the unraveling of what formed and guided Reagan with what drove Joseph to make a film about him: faith.

Indeed, the mystery in which we all live—God’s presence in our lives—drew Joseph into understanding Reagan’s story at a level that cried out to be told, albeit his interest in Reagan appeared at first to be a matter of happenstance.

On a family vacation, Joseph was caught in a speed trap driving through Dixon, Illinois, the town where Reagan grew up. He had to wait a day to see the local judge and pay the fine. Realizing they had been detained against his will in Reagan’s hometown, Joseph took his family to see the home in which Reagan lived and the beachfront of the Rock River where Reagan served during his teenage summers as a lifeguard, saving 77 lives from the tricky currents.

What turned Joseph’s interest in Reagan from a passing enthusiasm into a quest was the reading of Paul Kengor’s The Crusader: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of Communism. Kengor had done what other biographers failed to do, look deeply into Reagan’s formative years. His father’s alcoholism was known, but the depth of his mother’s Christian faith had been neglected. Her constant admonitions that her son not neglect God stayed with Reagan, even when his career in Hollywood and his marriage to Jane Wyman fell apart.

In the movie, he visits his mother at this low point in his life, confessing how poorly circumstances have turned out, abetted by his own failings. In the film she puts him back on his feet and once more into the fray, with the admonition: “Remember whose you are and whom you serve,” a line which Joseph’s borrowed from his own devout mother.

Kengor also discovered that Reagan had been inspired as an eleven-year-old by a Horatio Algier story, That Printer of Udell’s, a gift from his mother. It was about the son of an alcoholic, the young Dick Falkner, who finds faith in God and grows up to be a United States Senator. Reagan took that as a road map to his future. He went to his pastor and insisted on being baptized. Kengor also discovered the typescripts of the sermons Reagan had heard while growing up, which were replete with critiques of communism.

Reagan’s trajectory began to make sense: his resistance to a communist take-over of the Screen Actors Guild as president from 1947 to 1952; his naming of the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” in 1983 at a speech given to the National Association of Evangelicals; his 1987 Berlin speech in front of the Brandenburg Gate, where he rallied the world by proclaiming, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Reagan was not religious in the manner of Jimmy Carter, who popularized the phrase “Born Again” and spoke often of how much teaching Sunday school meant to him. When anyone claimed Reagan as “God’s man,” critics quickly pointed out that he rarely attended church during his presidency. His wife Nancy’s consultations with astrologers attracted a lot more attention than Reagan’s Disciples of Christ formation.

Still, Joseph believed Kengor’s biography was the golden key to understanding Reagan and telling his story. Not long after he read the book, he wrote Kengor a note congratulating him. He was glad Kengor had written his book, Joseph said, because now he no longer needed to do so. Soon after, the producer acquired the book’s film rights. In 2010, Reagan: The Movie was announced in The Hollywood Reporter, the link picked up by Drudge, and the story went viral from there.

Joseph came to wonder if what had first seemed happenstance had been orchestrated. Divine providence—shorthanded in the book as DP—had led him into this venture. He admits that he also presumed as much with other projects that came to nothing, so, blessedly, there’s nothing like the cocksureness of those who proudly declare, “God told me to…” But he had become convinced that making a movie about Ronald Reagan might be something he was supposed to do. This didn’t dispel all doubts later—not by a long shot.

At that point in his career, he had been a film executive on the first two Narnia films, worked as the producer of the inspired by soundtrack for Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ, and was credited as a producer on films starring the likes of Martin Sheen and Jerry Lewis. Reagan would be his first time helming a feature film on his own.

Much of the next fourteen years, until production finally began in 2020, was taken up with developing the script, finding the right director, recruiting name actors for the lead roles, and fundraising.

The great pleasure of Making Reagan is the transparency with which Joseph recounts this arduous process. If the reader wants to know what it’s like to have countless promises made for funding only to see the anticipated wire transfers never hit the bank, to have funding made contingent upon terms that keep changing in an effort to wrest creative control, or engage in endless talks with major studios who after months and months prove unable to achieve internal consensus there’s no better primer than Making Reagan.

Likewise, Joseph’s stories about courting actors and their agents over the same period as he goes through a succession of people who prove not right, uninterested, renege on their commitment, or attach themselves to the project in order to turn it into a star vehicle for them are instructive as to how Byzantine such negotiations can get.

Joseph found it particularly difficult to cast the lead, a make-or-break choice in a biopic. Think of Gary Oldham in The Darkest Hour or Jamie Foxx in Ray—two stunningly good performances. Or the contrary, John Travolta’s disastrous turn in Gotti. The subjects of biopics are so well known that the audience feels an inherent possessiveness toward them, which raises the bar for an actor whose job is to make them come alive in a new way on screen.

Joseph approached a litany of A-list stars to play Reagan, including Oldham (despite his short stature and limp) and Christian Bale.

When his first choice, Dennis Quaid wasn’t available, he thought he had found his Reagan in Nicolas Cage. After a preliminary meeting with Cage’s agent, Joseph met the actor in Las Vegas and Joseph found Cage approachable, friendly, and apolitical enough not to have in-built prejudices against taking on the assignment. They came to an agreement in principle. Months later, Cage’s manager abruptly informed Joseph that Cage was out, without providing an explanation.

Oddly enough, Cage’s seeming acceptance of the lead role led to Joseph losing his first choice as director, John G. Avildsen. Known as the “King of the Underdog,” Avildsen was the director of the original Rocky—one of Mark Joseph’s all-time favorite films. Joseph arranged for Cage, Avildsen, and him to meet together to discuss the film, only to have Avildsen pull out of the meeting at the last minute without explanation. Avildsen later excused his absence on the grounds that it would be a “dishonor” to Cage even to discuss the possibility of their working together when he believed Cage completely wrong for the role. This episode convinced Joseph that working with Avildsen would prove untenable, and the search for a director began again.

So it goes, might be the response of other experienced producers. Much of the job is all about getting lead actors and the right director “attached” to a project while the script is rewritten (often, many times), production units lined up, distributors courted, the money raised, and so much time passes that the list of those “attached” changes multiple times.

Of course, Joseph’s task was complicated by Hollywood’s loathing of Reagan, but then actors have been known to drop out of pictures for every imaginable reason. Their elderly aunt may have questioned the picture’s box office success, and anyway, a Japanese beer company offered them a million dollars for a one-day commercial shoot in Osaka.

Where Joseph runs into an amount of trouble that should make strong men weep consists in his efforts to raise the picture’s $25 million production budget, and the equal amount needed for distributing and marketing the film (P&A).

The film, Get Shorty (based on the book by Elmore Leonard), is a brilliant comedic piece about the narrow (and often crossed) frontier between crime and filmmaking, and Joseph’s Making Reagan has its own rogue’s gallery of swindlers, extortionists, and people whose motives can only be described as fiscal sadism.

Early on, Reagan appeared to have a finance group which was prepared to put up $60 million in funding. The funder agreed to Joseph’s non-negotiable demand that he have full creative control, as well as the authority to direct the picture’s marketing and distribution.

Experience had taught Joseph that any attempt to give the “Hollywood treatment” to Reagan would vitiate the reasons for making it. He had seen the director of the first two Narnia films try to confound the author C.S. Lewis’s intentions—the genius who had made the books universally beloved. He had no intention of letting people who wanted to “deconstruct” Reagan portray him as the fool they wished he had been. Or mislead the millions who remembered Reagan as the greatest president in their lifetimes into believing the picture would not represent him as such. The latter didn’t even make business sense, but when it came to making pictures about conservatives that was Hollywood’s modus operandi—extend foot and blast with shotgun.

The initial $60 million funder seemed to be on the same page, but over the next seven months of negotiations he kept trying to change the terms of their agreement, first asking for control over distribution and marketing, and finally demanding full creative control.

Some thought Joseph should take the money and run—he could use the payday to make another picture on his own terms. Instead, he walked.

This happened not once, but twice, the second time with a purported billionaire, who actually had only $100,000 to invest, but still thought he could remove Joseph as producer and bring in his own people.

These go-rounds were about power. A more interesting and elaborate plot involved a sophisticated grifter: a woman who was thought to be the daughter of a hedge fund billionaire. She was prepared, she said, to invest in a slate of ten films. Her venture into filmmaking was announced at a lavish party in Nashville, where Joseph, and other filmmakers whom she had promised to fund, gathered to collect their multi-million-dollar checks. Lawyers from one of the industry’s top law firms, Loeb & Loeb, were involved, contracts signed, and everything seemed on the up-and-up.

Delays began to mount, however.

For your copy of MAKING REAGAN, Click Here

One day Joseph’s screenwriter drove by the funder’s offices and saw a For Lease sign in the window. The woman’s father turned out not to be a hedge fund manager but the owner of a Kinko’s in Knoxville. Joseph suspected that she had hoped other investors would take her last name as connecting her with the hedge fund manager and contribute millions to her “film fund,” which she could then pocket. This cost Joseph a year of delay.

Dealing with people who are power hungry or greedy makes a certain kind of sense: those are motivations anyone can understand, however deplorable they may be.

Some of those who promised the producer funding and never delivered present head-scratchers, though. A Monaco fashion model signed a contract to provide $5 million but then blamed the failure of the money’s arrival on transposed account numbers, which she purportedly sent an assistant to Miami to sort out. Joseph discovered she had previously been on trial in Finland for car theft from an estranged husband. Nothing was on its way or would ever be.

A funder from Canada promised $5 million. The producer had enough confidence in this source to announce the funding in The Hollywood Reporter, which created the impression that the film was now fully funded. Delay followed delay, however, and Joseph was left with nothing but further delays. What was the Canadian thinking? Did he simply get cold feet, change his mind, and find himself too embarrassed to admit as much? Or what? I characterized such behavior as “fiscal sadism”; to play Lucy-and-the-football like this (with Joseph as the inevitably disappointed Charlie Brown) is cruel. As Proverbs has it, “Hope deferred makes the heart sick, but a desire fulfilled is a tree of life (13:12).” Few know just how sick the heart can get better than filmmakers.

There’s a question to be asked that pertains not so much to the miscreants Joseph encountered as to conservatives who in theory should want Ronald Reagan’s story told. The producer was proposing a fair portrayal of Ronald Reagan. Could any subject be more on the nose for conservatives? Could there be a more obvious example of pent-up demand than the millions who saw the Reagan revolution as one of the most positive developments of their lifetime? An event that had not one—not one—feature film made about it? What were the many potential funders who said “no” thinking?

“Conservatives are conservative with their money” has now become a commonplace in explaining why projects like Reagan find funding so difficult to recruit.

I disagree. The reluctance of conservatives to fund such projects should not be written off as part and parcel of their risk averse nature but attributed to their lack of prudence. Dana Carvey made people laugh with his imitation of George H.W. Bush tenting his fingers and sputtering, “Wouldn’t be prudent.” The joke depends on people associating “prudence” with “timidity.”

Actually, prudence is the virtue of being able to assess risk correctly. Not just the immediate risk at hand but risk in the widest possible frame.

The imprudence of conservatives in backing cultural projects such as Reagan has nearly resulted in the loss of the great Western tradition responsible for making so many conservatives rich. It’s taken cancel culture, the de-banking of those the government deems suspicious (this has already happened much more than has been widely acknowledge, according to venture capitalist Marc Andreeson), and people marching by the thousands in support of antisemitic savagery to awaken conservatives even partially out of their self-satisfied slumbers. Even now, former left-leaning entrepreneurial titans such as Elon Musk, Bill Ackman, Joe Lonsdale, and Doug Leone understand the existential risk posed by progressivism better than traditional conservative with their trillions locked up in donor advised funds.

In our digital age, wealth can disappear with a keystroke. Wake up!

Joseph still didn’t have the entire production budget in hand when he took a leap into the dark and started production on Reagan in 2020—in the midst of the Covid crisis.

This is not an unheard-of practice in filmmaking, since the momentum of having scenes in hand to show potential funders can help secure a last piece or two of funding. Still, it must have been nerve wracking.

Joseph piled his wife and kids and 92-year-old mother into an RV and took off from California to Guthrie, Oklahoma, where he had found a Masonic Temple whose meeting hall and collateral rooms could serve as the sound stages for most of the scenes in the film.

Joseph faced some tough calls in making Reagan, including abandoning the first script and starting over with a second screenwriter, as well as parting with personal heroes like John Avildsen. He has the backbone necessary in a producer.

The tyrant Louis B. Mayer he isn’t, however, which is a happy thing. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a producer more grateful for his ability to work in film. He finds the camaraderie of the “temporary family” assembled as among the chief pleasures of movie making, citing having meals together and taking side-trips during off hours as among the best parts of the work. He kept closer to the set with Reagan than on other projects, as he had been so intimately involved with developing the film and seems to have enjoyed every moment.

As a result, we get a particularly granular look in Making Reagan at the process. “Step by step, day by day, scene by scene,” Joseph writes, “the film took shape. As I watched the dailies, I was floored by what we were creating together and how amazing filmmaking truly is; there’s something magical in re-creating scenes from fifty and a hundred years ago; to first imagine what was said and then bring those scenes to life with people whom you admire.”

Troubles are never far from his mind, though, and he became a peripatetic, walking everywhere in Guthrie, trying to unwind from the worry.

Things did go wrong. As a result of Covid, the set had to close down twice for ten days so that members of the crew who took ill could be isolated and everyone else clear testing before filming could be resumed.

His love of the work kept him going, though. This comes through in the many appreciative comments he makes on how the actors help flesh out aspects of the film. Justin Chatwin, who played Ronald Reagan’s alcoholic father, helped toughen up the man’s portrayal, drawing on his own experiences of having an alcoholic father whose unpredictable behavior kept his family constantly anxious. Dan Lauria, who played Tip O’Neil, thought to clutch his rosary beads when visiting Reagan in the hospital after the assassination attempt, a natural thing for a Catholic to do but something Joseph would never have thought of as a Protestant. The inimitable Jon Voight noted the deadness in the eyes of the Russians he had met in the days of the old Soviet Union and their disinclination to look at anyone directly, which figured into his own remarkable portrayal of a longtime KGB agent.

Joseph expresses his gratitude for these and many other instances of the collective creative process that’s a hallmark of filmmaking.

Penelope Ann Miller, who plays Nancy Reagan, invested herself in the role to the point that she watched every piece of film she could find on Nancy Reagan and read voluminously about her, and as a result gives what I think is the best performance in the film.

I never liked Nancy Reagan from what I knew of her as a public figure. I thought her humorless and given to putting on airs. I could never figure out why Reagan even liked her, much less be the doting husband he so obviously was.

Yet, Miller drew me into how Nancy Reagan provided both the protective love Reagan needed and also a flinty suspicion of others who she suspected, often rightly, of using Reagan’s overly trusting nature against him. Like Reagan’s mother, Nancy could always put him back together and send him once more into battle. When he betrayed his principles in the Iran-Contra scandal, she told him both to tell the truth and fight—a rare political strategy and one that worked. The president’s son, Ron Reagan, is said to have quipped that without Nancy Reagan his father might have ended up the host of Unsolved Mysteries instead of the president of the United States.

The deepest relationship that Joseph developed was with his star, Dennis Quaid. They came to know about each other’s families, particularly the importance for each of their mothers. Joseph also met Quaid’s wife-to-be, Laura Savoie, while they were still dating, and she so impressed Joseph as being just what Dennis Quaid needed—and his own film, of which she was a big supporter—that he urged his star not to let Laura get away. Their relationship became as close as was needed while never compromising their distinct roles, which enabled Joseph to continue giving unfettered advice and direction where needed.

The film improved at several points as the result of their collaboration. Most notably, before shooting Reagan’s famous speech in Berlin before the Brandenburg Gate, Quaid, going over Reagan’s speech, noticed a passage to which neither had paid sufficient attention.

In it, Reagan describes how the East Germans erected a television tower at Alexander Platz that stood high above the entire city. The tower had one major fault, however. No matter what kind of paints and chemicals were applied to the glass sphere at the very top, when the sun struck the sphere, the light made the sign of the cross. “There in Berlin, like the city itself, symbols of love, symbols of worship, cannot be suppressed,” Reagan commented.

The president went on to predict that the wall would one day come down. “For it cannot withstand faith. It cannot withstand truth. The wall cannot withstand freedom.”

The film’s rendering of Reagan alluding to this symbol and then demanding, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” is certainly the high point of the film. The movie cuts from Reagan in Berlin to his young speech writers watching it on television, who jump out of their seats with joy. The audience is right there with them. It’s a sequence for which the film should long be remembered and celebrated.

With a nod to Ziskin. Making Reagan makes a strong case that certain movies, at least, are called into existence. For certainly, in recognizing that Reagan’s Christian faith was the key that unlocked his “inscrutable” personality, Joseph found himself in possession of a story that he felt obliged to tell.

Without Reagan’s faith he could not have had the discernment and the courage to call the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” He could not have confidently proclaimed that the crushing force of totalitarianism must ultimately give way to the immaterial but greater power of faith.

Knowing this, believing this, Joseph himself found the faith and courage—the calling—to tell the story as it had never been told before.

Nineteen years. As Joseph considers the hand of providence in the making of the film, he acknowledges that many things happened that he resisted yet turned out for the best; among them, the film finally hitting theaters in an election year. Even the tremendous disparity between the audience’s overwhelming approval of the film and some critics panning the film out of hatred for Reagan redounded in the film’s favor. That made for a story of elites trying to suppress a film audiences loved, which drove even more people to go see it.

All’s well that ends well, one might say.

Or: "We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose” (Rom 8:28, NRSV).

This leaves me double minded.

I have no doubt that God used Joseph’s epic struggle to accomplish his main goal, which is always our transformation into his likeness. In that sense, yes.

But if we are ever to have anything like a healthy Western culture again, it simply cannot take 19 years to make a movie about Ronald Reagan. That’s not God’s fault. That’s ours. Divine providence shouldn’t be used as an excuse not to write checks. Shame on all those who turned Joseph down-those to whom 25 million dollars is like a quarter to the rest of us. Joseph has reported that some of them turned him down while saying they couldn’t wait to watch his film in theaters. Others reported back to him with gratitude after watching it in the theater. Each one of them should hang their heads in shame. But if a new culture that embraces storytelling emerges as a result of this film and book, perhaps it will all have been worthwhile. Let’s hope that happens.